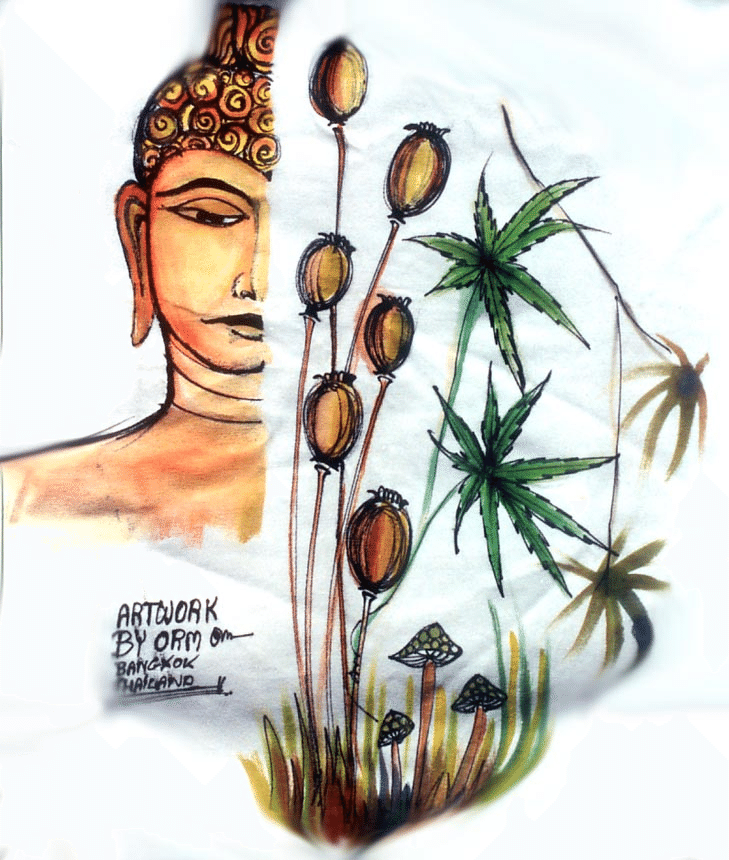

A hand-painted t-shirt depicting magic mushrooms for sale in Thailand.

Psilocybe samuiensis was discovered on the Thai island Koh Samui.

Western mycophiles traveling the world were quick to find magic mushrooms throughout Southeast Asia. In these regions, it is unknown if the indigenous populations had previously known about or used these mushrooms for entheogenic purposes because studies occurred after the proliferation of Western presence. Locals who have access to these species make a living collecting and selling them to Westerners. Some restaurants even sell food using them as ingredients. In this way, regions containing species of Psylocibe become known for the mushrooms which attracts more tourism (Allen & Gartz 1977). In Thailand, mushroom use is heavily associated with tourism and foreigners, with only moderate use among local teenagers. Tourists can purchase art and garments depicting the mushroom, especially in certain regions. "Shroom Shakes" are a popular way to purchase and consume mushrooms in Thailand as well (Allen & Merlin 1992). Bali is another popular site for mushroom tourism, however, most Balinese people will not partake in the mushroom. In Balinese culture, they value clear-headedness and are unlikely to use inebriating substances. Similar instances of mushroom tourism can be found elsewhere in Indonesia as well as Laos, India, and Nepal (Allen & Gartz 1977). Thus, a global market has been cultivated which sells not only psychedelic experiences but also exoticism and ethnic fetishization (Faudree 2015).

Allen, J., and Gartz, J. (1977). Magic mushrooms in some third world countries. Ethnomycological Journals Sacred Mushroom Studies, 6. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336281368_Magic_Mushrooms_in_Some_Third_World_Countries

Allen, J., and Merlin, M. (1992). Psychoactive mushroom use in Koh Samui and Koh Pha-Ngan, Thailand. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 35, 205-228.

Faudree, P. (2015). Tales from the land of magic plants: textual ideologies and fetishes of indigeneity in Mexico’s Sierra Mazateca. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 57(3). 838-869. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43908373

An advertisement in Bali for magic mushrooms.

An advertisement for magic mushroom milkshakes in Thailand.